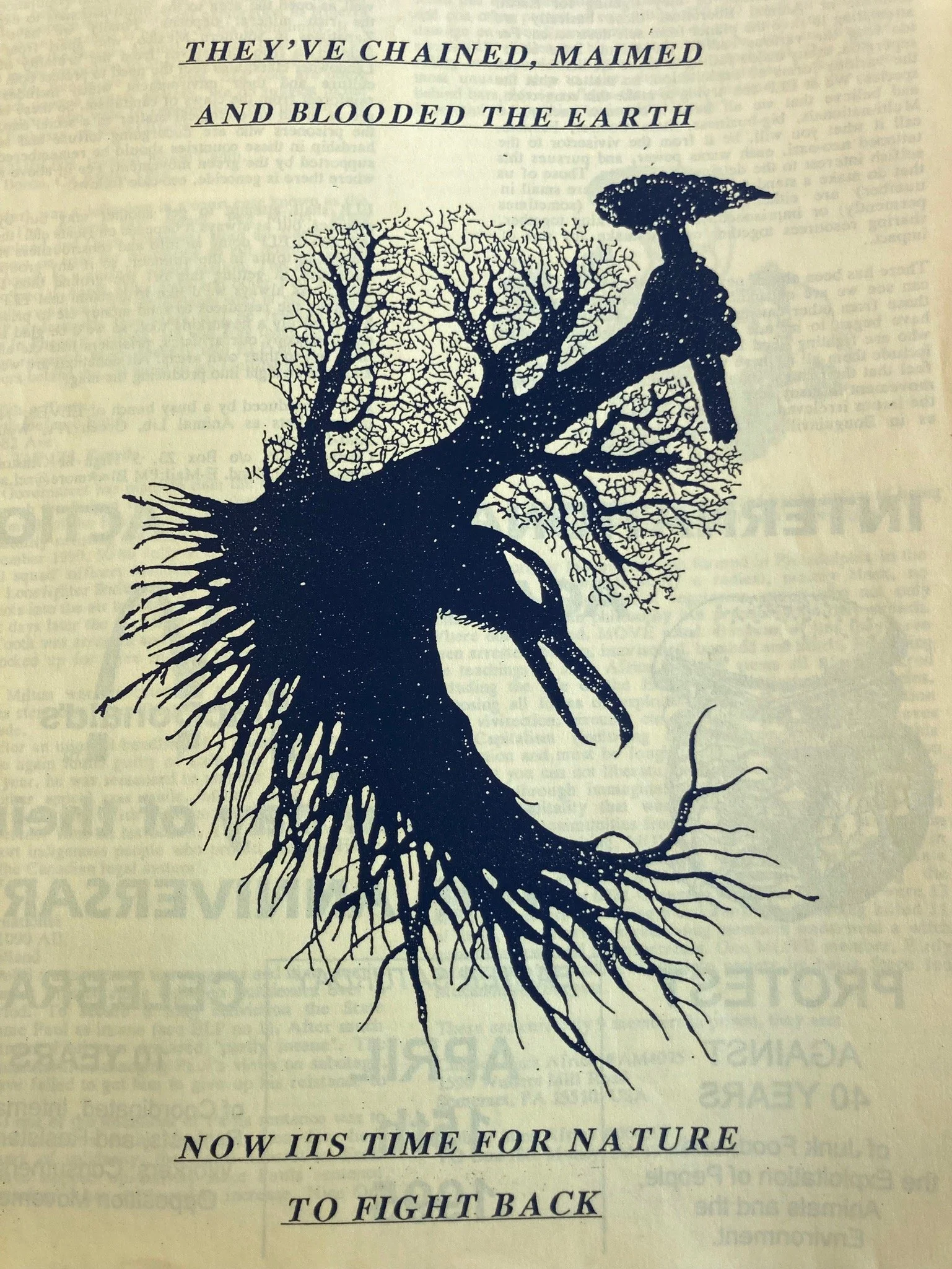

Global Ecology not global Economy

MayDay Rooms

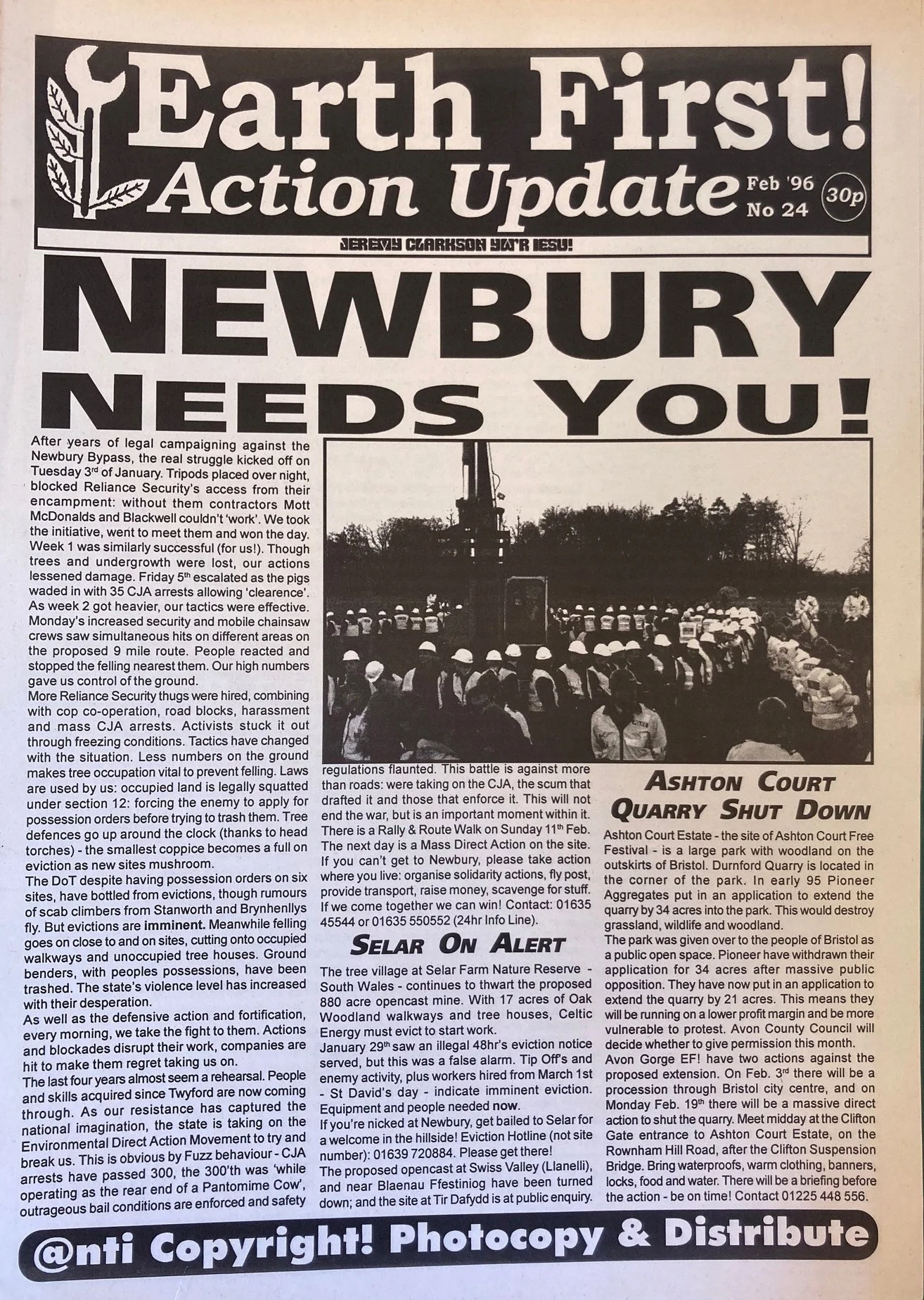

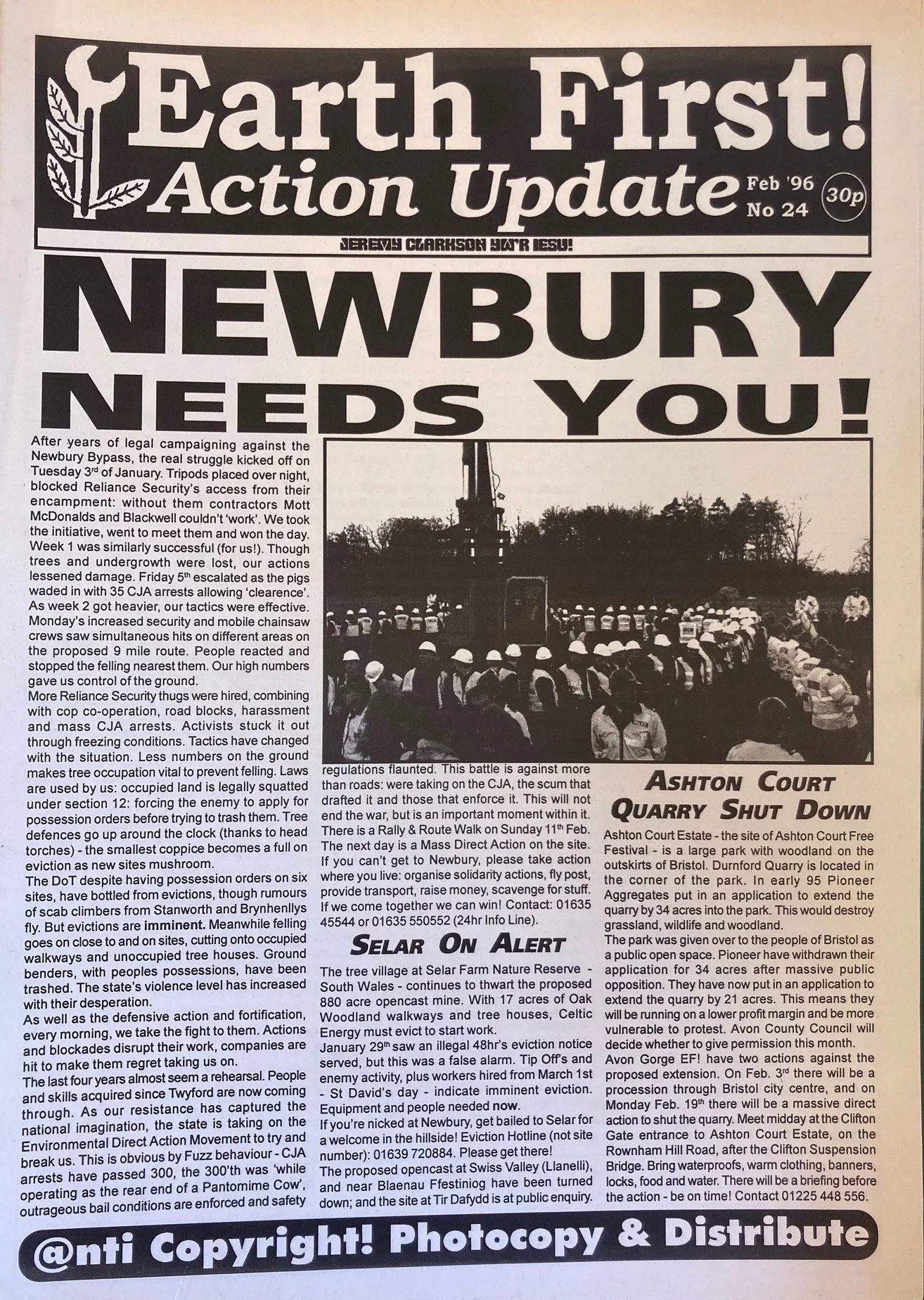

In January 1997, Friends of the Earth called a rally at the construction site of the Newbury Bypass. The plan was for a candlelit vigil, followed by speeches, and then a march to the building site to tie ribbons and messages to the fence. The event was billed as a one-year anniversary reunion for all the activists and campaigners who had spent the previous winter occupying tree houses, dodging vast armies of security guards, attaching themselves to barrels full of concrete and using many other inventive tactics in an attempt to slow or stop the felling of more than 10,000 trees to make way for the construction of the road. The eviction of over 30 different treehouse camps along the route of the planned bypass from January to March of 1996 had become a national cause celebre, attracting thousands of activists in freezing conditions to try and stop the clearances.

But the camps had been evicted, the trees had been felled. The full resources of the state had been deployed, at a cost of more than £30 million in policing and security, resulting in over 700 arrests. And what was once people’s woodland home had been turned into a giant muddy wasteland populated by yellow diggers grinding slowly past charred tree stumps.

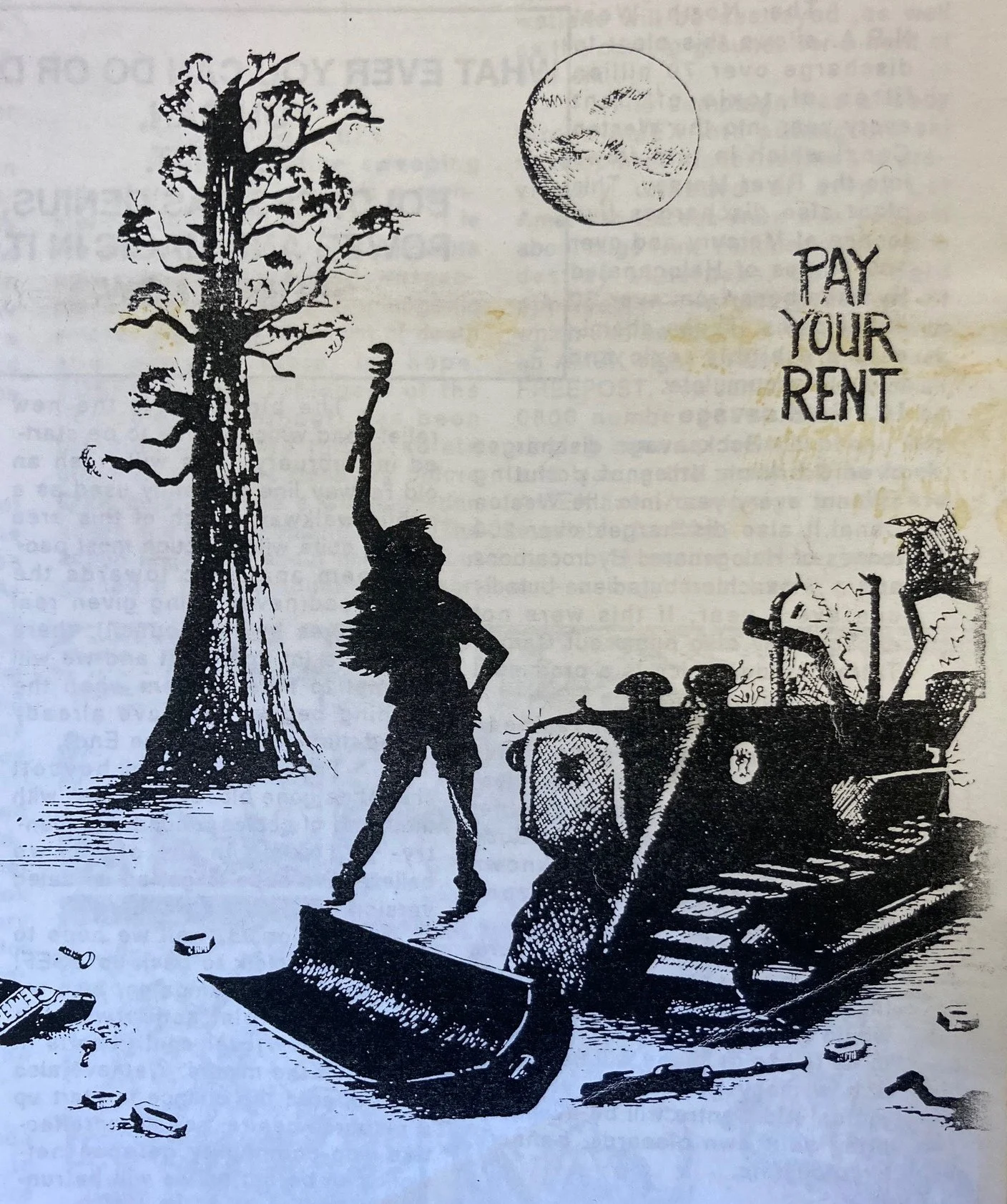

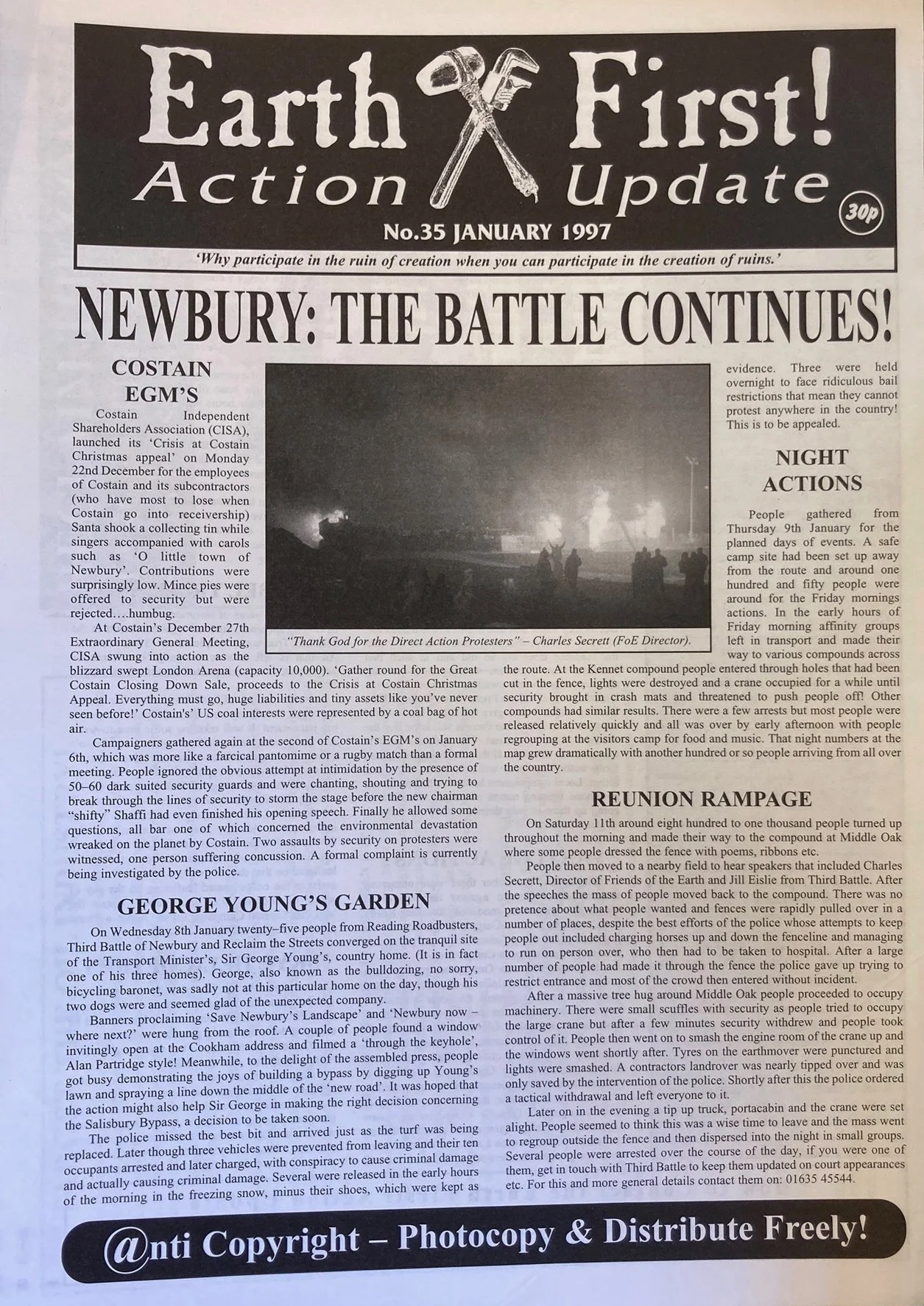

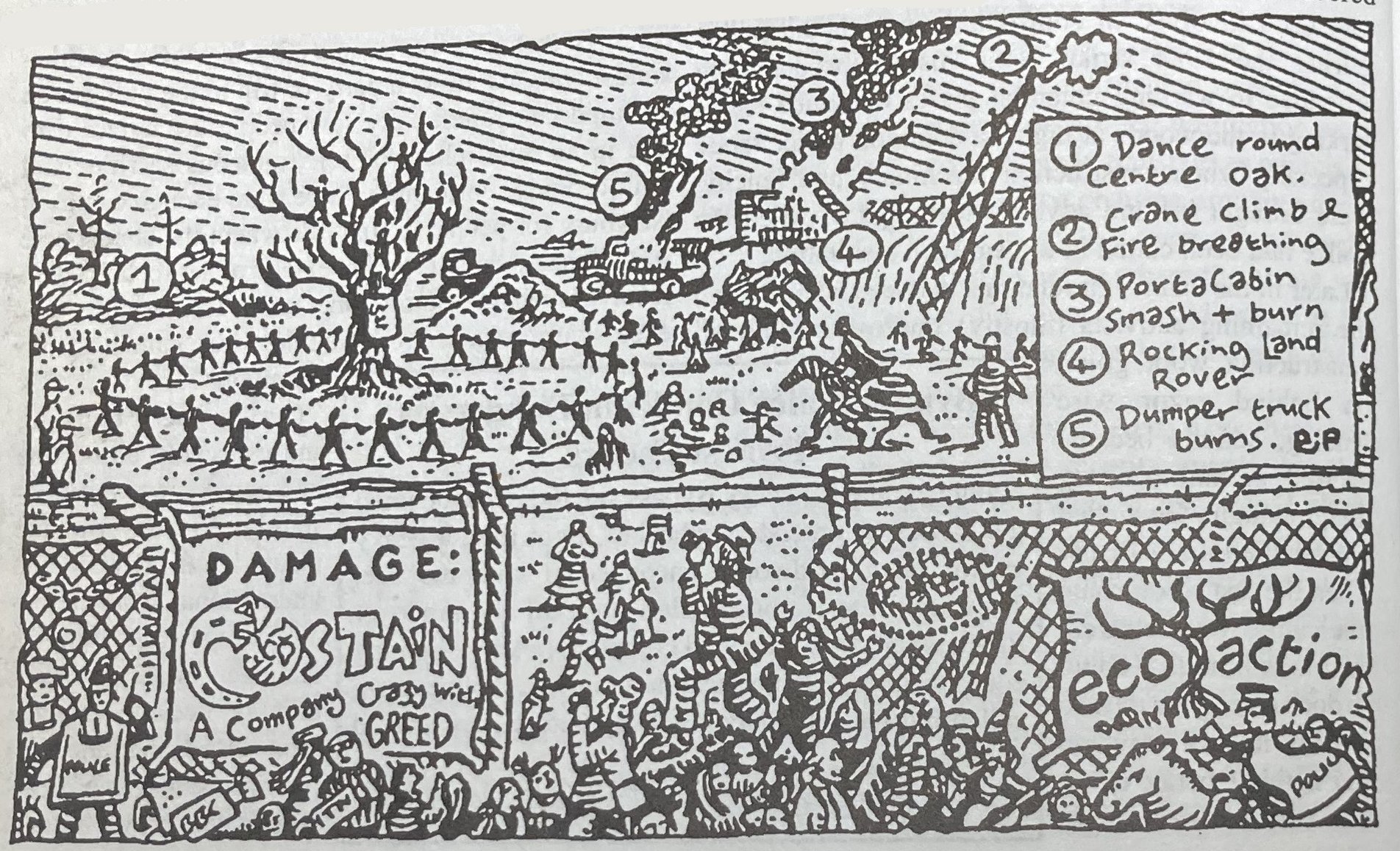

The rally to mark the anniversary did not go entirely according to the plan imagined at the Friends of the Earth head office. The fences intended for ribbons and messages were swiftly toppled, and hundreds of activists invaded the construction site, turning it into an impromptu party as they danced atop the hated diggers and cranes. As some danced, played music or lit up the evening with fire breathing, machinery on the construction site was being dismantled, smashed and ultimately set on fire.

The police stood by powerlessly as the flames of a burning crane lit up the night sky to howls and whoops.

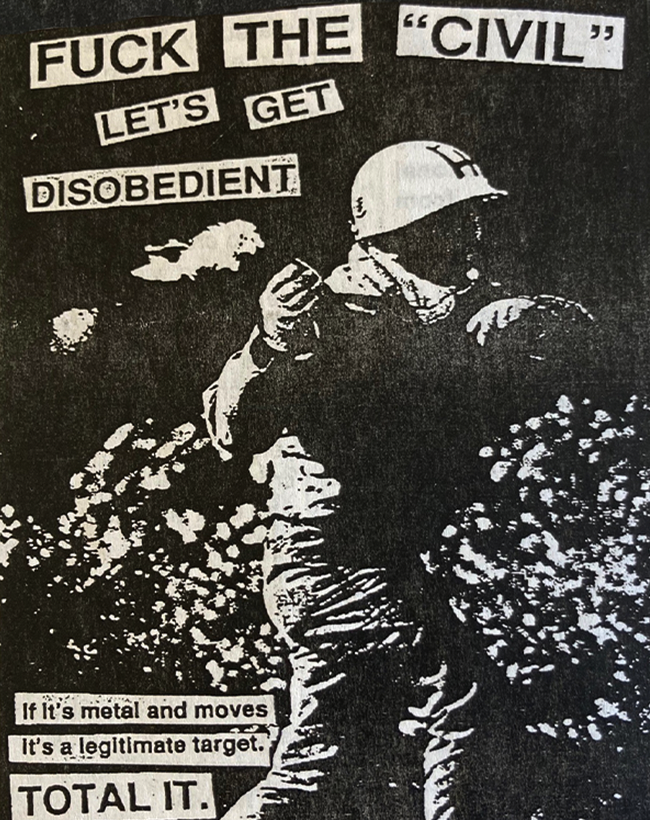

The ‘Reunion Rampage’, as it became known, was just one iconic moment of the 1990s ecological direct action movement; a moment of revenge, a howl of rage for a destroyed landscape. But it also shows the surprising alliances; the mad creativity; the deeply felt connection to nature; a newly discovered community; and the high level of militancy characteristic of the time.

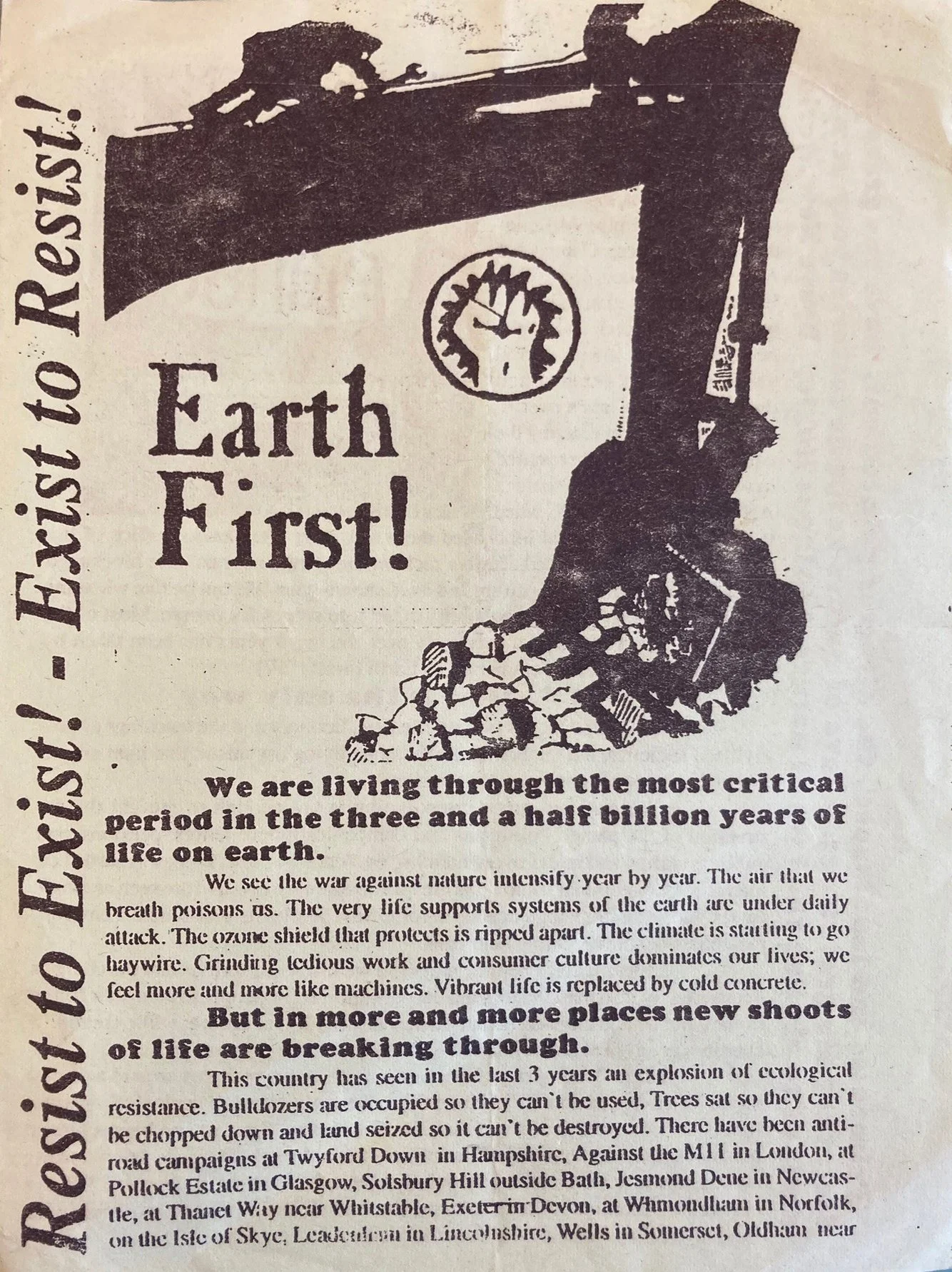

By the 1990s, the radical environmental groups of the 1970s, like Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace, had grown into international NGOs with large headquarters, slick branding, and fundraising operations. They were increasingly unwilling to rock the boat politically and largely treated their supporters as a mere source of direct debits. A new generation, increasingly concerned about the environment, was dissatisfied with these vehicles, and in the early 1990s, a more radical ecological movement emerged. Earth First! – a no-compromise wilderness defence organisation imported to Britain from the USA– founded a handful of local groups amongst those frustrated with the meekness of mainstream environmentalism and carried out some increasingly ambitious actions. However, it was really opposition to the Tory government’s 1989 road-building plan, ‘Roads for Prosperity’ – which Thatcher boasted was the "biggest road-building programme since the Romans” – that catapulted ecological struggle to become the main radical political movement of the 1990s. And it was living in camps and tree houses, on the sites of planned developments, that became the defining image of those years.

From 1992 onwards, camps popped up across England, Scotland and Wales against roads, airports, open-cast mining and other ecologically destructive developments. The camps were defensive, but also ‘prefigurative’: people were experimenting with a model of a more ecological sustainable lifestyle – living in non-hierarchical, self-organised communities, close to nature. Protesters built highly elaborate and creative defences – double-level tree houses, walkways linking them, giant cargo nets suspended in the air, massive rickety scaffold towers, concrete lock-ons in tree houses or suspended by steel cables. And below ground, tunnellers started digging, building complex mazes under the trees full of steel doors, wrong turns and armoured bunkers. Evictions began to take weeks, costing the state millions of pounds and requiring vast numbers of security guards, cops and bailiffs as well as specialist teams of climbers and cavers to remove protesters.

And yet, almost every single one of the roads opposed was built. The movement has been characterised as having a strategy of 'noisy defeats and quiet victories'. The state doesn’t like to be seen to back down to direct action and thus puts enormous resources into making sure that activists are seen to lose. But due to the scale of opposition, the whole vast road-building programme became increasingly discredited and expensive to build, so after Newbury, the government quietly shelved much of its £23bn flagship roads programme. The final coup de grâce was delivered as Labour took power later in 1997 and cancelled the remainder of the programme.

We have seen a similar effect recently with Just Stop Oil, the ecological direct action group the tabloids love to hate, famous for throwing soup on paintings and blocking the M25. Despite an incredible level of repression, prison sentences and whole new laws being passed specifically to outlaw their activity, their key (and incredibly moderate) demand of no new oil and gas exploration in the North Sea has quietly been met.

The state doesn’t want us to realise the power we have and will always pretend that any change had nothing to do with activists and that they were always going to do it anyway. If we accept their version of events, we are led to conclude that we are weak and that our activity should be limited to appealing to those in power for small changes. Thus, we see the critical importance of telling our own stories, remembering our own history and claiming our victories. When we come to see the enormous transformations that popular power and direct action have achieved, we realise that the power of corporations and the state is a fragile thing. It is maintained by a sleight of hand, designed to obscure the power we all have to remake the world.

Andrew Jamison is a historian and researcher currently cataloguing and exploring the 1990s ecological direct action movement with the MayDay Rooms.

MayDay Rooms is an archive of radical social movements and experimental culture. It has recently catalogued a new eco-anarchist collection of materials from the 1990s direct action movement. The story told above is only a small sliver of this wider history. For more, visit the MayDay Rooms’ unique collection of archive materials from the time: maydayrooms.org

If you have materials relating to the ecological direct action movement of the 1990s (such as posters, flyers or leaflets), then please contact MayDay Rooms at: in-formation@maydayrooms.org

Each issue we print 40,000 copies, worth £120,000 to our vendors. Your £3/month subscription is used to print 30 copies per issue, worth £90 for our vendors. We went from 1000 copies per issue in 2018 to 40,000 per issue in 2025. The only thing stopping us from doing more is money. With your support, we can go even further. Help us print and distribute more copies for free to anyone who wants to sell it by becoming a monthly subscriber.