A report from Rojava

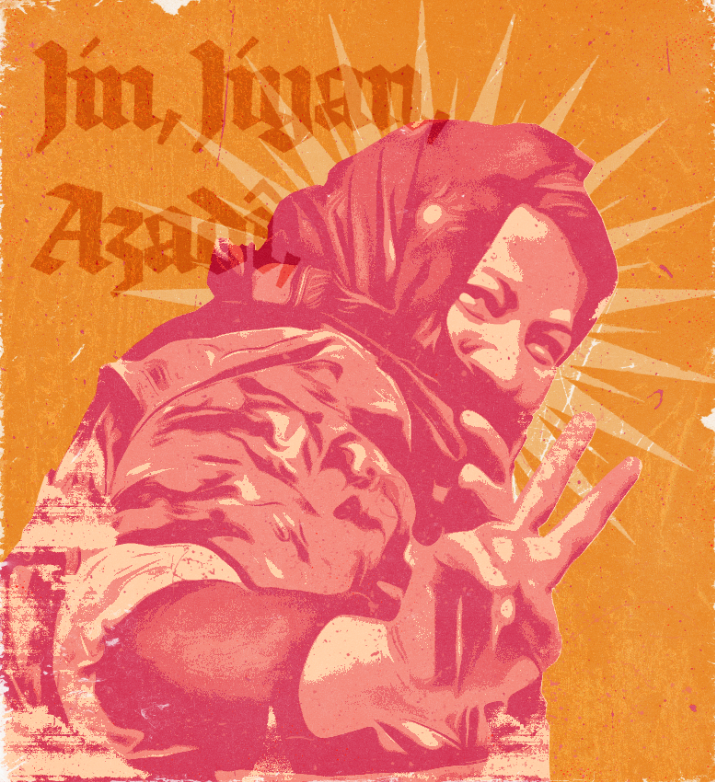

Article: Nevis Morel. Photo: KurdishStruggle. Illustration: Rory Robertson-Shaw

Since the fall of Bashar al-Assad's regime in Syria in December 2024, the future of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), also known as Rojava, remains uncertain. While there is no shortage of geopolitical analysis about the situation, one crucial voice is often overlooked—the approximately five million civilian inhabitants of the region. Their voice could be crucial for the future of Rojava, an area that has established an administration based on a bottom-up, directly democratic system that aims to empower its citizens. However, evaluating this from afar is difficult, amongst media reports riddled with various biases. Some praise the mass civilian support for the administration near the strategic Tishreen Dam in the west of Rojava, while others accuse the administration of holding a nationalist and separatist agenda.

So, when the women's organisation Kongra Star shared a call for international activists and journalists to come to Rojava to cover the ongoing crisis, I jumped on the opportunity to see with my own eyes how civil society is experiencing the developments of the region.

Before leaving, I feared I would witness the final moments of a revolutionary project on the brink of collapse. Part of this fear stemmed from the direct military threats. The Turkish state has waged a genocidal war against the Kurdish people—an ethnic minority in Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria—and has been bombing the AANES (home to Syrian Kurds) since the North and East first gained semi-autonomy from Syria with the start of the Rojava Revolution in 2012. Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which pushed out the Assad regime last December, are Turkey’s ally, and Turkish military harassment of Rojava has intensified in the past few months. Additionally, there is concern that even if the region avoids direct military annihilation, the ideals of radical democracy it embodies could be neutralised.

The agreement signed in March between HTS and the AANES shows both sides' willingness to move towards peace in the region. This agreement also guarantees basic civil rights previously lacking for Kurdish inhabitants of Syria, such as language rights and increased citizenship access. However, reports suggest that HTS is demanding, in exchange for these rights, that the autonomous administration cede control of their Arab-majority territories. Over the past 15 years, Rojava's democratic project has developed a model of multiethnic coexistence and local autonomy, aiming to overcome religious conflict and ensure equal representation for all, regardless of ethnicity. Reducing this initiative to only Kurdish-majority areas could risk transforming it into a nationalist movement focused solely on civil rights for Kurds, sidelining its universalist ideals. This was my concern before my arrival.

Upon arriving, however, the situation appeared quite different. I had the opportunity to interview several civil society organisations with different focuses, yet all expressed unwavering support for the confederalist system in place. While the recent agreement seems to have garnered general approval, caution remains present, with heavy scrutiny regarding the ongoing negotiations. I spoke with Malek Salah, co-chair of the Washokani camp for internally displaced people, about the significance of refugee camps in Rojava. She expressed confidence in the AANES' ability to refuse agreements that grant excessive control to HTS over the camps and threaten the political autonomy of their inhabitants. However, she also stated, "If that is not the case, we will not accept it." Such readiness in favour of disobedience may be surprising, but is in line with the Kurdistan Liberation Movement's philosophy, which advocates scepticism towards blindly following authority.

The reluctance of the region’s inhabitants to accept a potential erosion of their democratic system is also rooted in the shared experience of loss. Almost everyone there, Kurdish or not, has lost a loved one in the struggle against authoritarian conservatism. It's what Rojava is most well-known for: Rojava's army, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), fought back and ultimately defeated ISIS between 2013 and 2019. This came at the cost of around 11,000 fighters, referred to as martyrs by the movement. The sentiment of debt to the martyrs is absolutely omnipresent in the region. Each commune (a sort of neighbourhood assembly that constitutes the basic unit of the democratic confederalism system) is named after a local martyr, and there are dedicated cemeteries for martyrs in every city. This creates a profound sense of responsibility to continue their struggle. When I asked Avin Swaid, a high-ranking diplomat representing the Women’s Department of the AANES, whether she feared the agreement might lead to a loss of autonomy for Rojava, she simply replied, "We have lost thousands of martyrs here. Do you think the people will bend their heads down and accept it?"

A similar sentiment was expressed by Ronahi Hasan, Kongra Star's head of diplomacy. She believes the special importance that the Kurdistan Liberation Movement places on building up a culture of widespread participation in politics, rather than blind obedience to states, however benevolent they claim to be, has given the people of the region much experience in responding to attacks on their freedom.

Many people in Rojava have lived under direct occupation by ISIS and know full well the horrors of fascism. They also know what it is to rise up against it and struggle for democracy. For many, there is no going back.

While it's challenging to gauge the average resident's opinion on the current situation, the determination of the local organisations I have encountered suggests that the administration is held to a high standard by the community. They may enjoy substantial popular support, which could enhance their negotiating power against the HTS. However, if they fail to uphold the revolutionary ideals they have championed, they could face popular uprisings.

It remains uncertain how the AANES would respond to the potential for mass dissent, and I won’t make predictions about the future of Rojava here. However, experience has shown how giving people the tools to rise up and defend themselves is a crucial strategy for any revolutionary movement aiming to protect itself against the dangers of normalisation, authoritarianism, or co-optation.

Nevis Morel is an organiser living in Edinburgh who works with popular resistance movements against imperialism. They have been involved with the Kurdistan Liberation Movement for several years and travelled to Syria in March as part of a women’s delegation to report on the situation on the ground.

Your £3/month subscription is used to print 30 copies per issue, worth £90 for our vendors. We went from 1000 copies per issue in 2018 to roughly 40,000 per issue in 2025. The only thing stopping us doing more is money. With your support we can go even further. Help us print and distribute more copies for free to anyone who wants to sell it by becoming a monthly subscriber.